Shaton, Maya (2017). “The Display of Information and Household Investment Behavior,” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2017-043. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, https://doi.org/10.17016/FEDS.2017.043.

[via Stefan Zeisberger]

Abstract

I exploit a natural experiment to show that household investment decisions depend on the manner in which information is displayed. Israeli retirement funds were prohibited from displaying returns for periods shorter than twelve months. In this setting, the information displayed was altered but the accessible information remained the same. Using differences-in-differences design, I find that this change caused reduction in fund flow sensitivity to past returns, decline in trade volume, and increased asset allocation toward riskier funds. These results are consistent with models of limited attention and myopic loss aversion, and have important implications for households’accumulated wealth at retirement.

Throughout the paper I distinguish between available and attainable information. I denote as available information the raw information agents observe (the information that “falls from the sky”). Attainable/Accessible information refers to the whole information set to which investors have access.

No more 1-month returns, only ≥12 months returns

I explore how changes to information display affect household trading behavior and asset allocation for retirement savings. I exploit a natural experiment; starting in 2010, the regulator of Israel’s long-term savings-market prohibited the display of retirement funds’ returns for any period shorter than twelve months. Previously, 1-month returns were prominently displayed on a monthly basis as a measure of funds’ performance.

The intent of this regulation was to allow investors to examine fund’s investment policy over a longer horizon.

The regulation was highly enforced across different venues

Easily extracted?

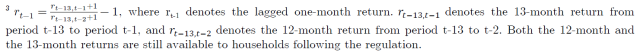

Households could still easily extract the 1-month return from reported information.3 Hence this new regulation represents a shock to the salience of information rather than a change to the information set accessible to investors. (…)

data available to households following the regulatory change are sufficient to extract the 1-month return

Ermm, “easily” in this context is this according to footnote 3:

Typically any change to manner in which information is displayed is associated with changes to the attainable information set, thus making it difficult to disentangle between the two.

Methods

I use a differences-in-differences research design in which retirement and mutual funds are the treated and non-treated groups respectively (…) use mutual funds, which were not subject to the regulation, to control for unobserved omitted variables.

347 retirement funds and 1177 mutual funds on average in any given month. The average retirement fund has $116.7 million in AUM, whereas the average mutual fund has $30.3 million in AUM. Additionally, we see that the average retirement fund trade volume is $1.9 million, while the average mutual fund has a trade volume of $5.163.

The data include the following variables: 1-month return, 12-month return, net fund flow, inflow, outflow, assets under management, volatility of past returns, and equity exposure.

Typically any change to manner in which information is displayed is associated with changes to the attainable information set, thus making it difficult to disentangle between the two.

Effects

- I show that retirement fund flows were sensitive to past 1-month returns prior to the regulation. Fund flow sensitivity to past 1-month returns significantly decreases following the new regulation (…) Effect 1-month returns approximately zero after the shock to 1-month returns’ salience. (…) Households no longer use past 1-month returns when making their investment-decisions once these are no longer salient.

- Using the standard differences-in-differences specification, I find that trading volume decreased by 30% compared to the control group following the regulatory change.

- Net flows into riskier retirement funds increased significantly following the regulation compared to the control group. I show that this net effect primarily results from a significant increase in flows into riskier retirement funds rather than a decrease in flows out of these funds.

- Funds’ flow sensitivity to past 12-month returns significantly decreases.

Absolute salience

Explanation for #3 (riskier asset allocation): The change in performance display is also related to households’ perception of losses. Typically, losses are more prominent when returns are observed at shorter horizons, e.g., 1-month horizon versus 12-month horizon. Given that empirically 12-month returns tend to be smoother than 1-month returns if the regulatory change influenced how salient losses are to households, it may potentially have affected households’ perception of retirement funds’ risk profile.

12-month returns are smoother and less flashy than 1-month returns, and are thus less salient in absolute term.

DellaVigna (2009) points to two caveats inherent to any attempt at estimating

a proxy for attention and salience (not a problem in this paper):

- Measuring the salience of information often involves a subjective judgment

- Generally any model of limited attention can be rephrased as a model of cost in which less salient information displays higher costs.

Policy: Extent & manner of disclosure

I present empirical evidence that a regulated change in the display of retirement funds’ past performance can significantly affect households’ trade volume and risk-portfolio allocation.

Regulating the display of information is relatively benign compared to alternative regulatory interventions

Unsophisticated investors could possibly be manipulated by the mere display of information.

Discussions surrounding transparency and disclosure requirements are generally centered on the extent of information given to investors. The results of this paper suggest that the manner in which information is displayed to investors should be part of [transparency and disclosure requirements] discussions as well.

Fairly low-cost changes in the display of past performance information could have a relatively large impact on households. I should emphasize that my paper does not address the question whether households’ decisions were optimal prior to or following the regulatory change.

It is key that policymakers acknowledge that the way information is displayed can potentially have a strong impact on household behavior

Ifs & Policy tool

- If one believes that households trade too much, at the detriment of their wealth, altering performance information display could be used to influence such behavior

- If one believes households engage in return-chasing behavior at the detriment of

their wealth, the results in this paper suggest changes to information salience could

serve as a tool to modify such behavior. - If one believes that individuals’ portfolio risk allocation is the result of cognitive biases and is not optimal. I show that the way past performance information is displayed to households could serve as a tool to influence their investment-decisions.

Conclusions

I provide real-world empirical evidence of how a regulatory shock to information salience affected household behavior.

I find that the shock to information display caused

- a reduction in the sensitivity of fund flows to short-term returns,

- a decline in overall trade volume,

- increased asset allocation toward riskier funds.