Célérier, Claire, and Boris Vallée. “Catering to Investors Through Security Design: Headline Rate and Complexity.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 132.3 (2017): 1469-1508.

Abstract

This study investigates how banks design financial products to cater to yield-seeking investors. We focus on a large market of investment products targeted exclusively at households: retail structured products. These products typically offer a high return under their best-case scenario –the headline rate– that is nested in a complex payoff formula.

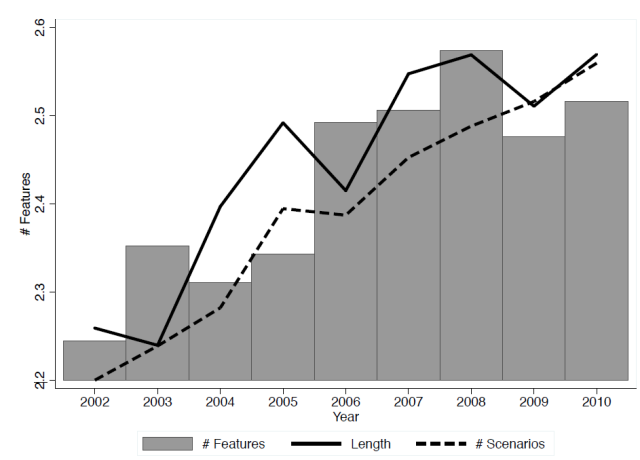

Using a text analysis of the payoff formulas of the 55,000 products issued in Europe from 2002 to 2010, we measure product headline rates, complexity and risk. Over this period, product headline rates depart from the prevailing interest rates as the latter decrease, complexity increases, and risky products become more common.

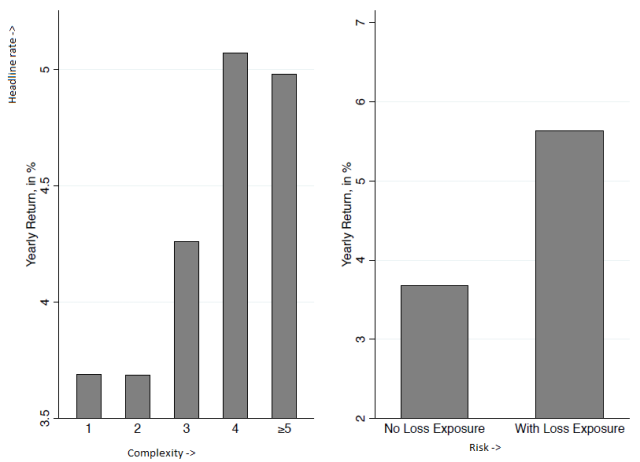

In the cross section, the headline rate of a product is positively correlated with its level of complexity and risk. Higher headline rate, more complex, and riskier products, appear more profitable to the banks distributing them.

Our results suggest that financial complexity is a by-product of banks catering to yield-seeking investors.

On structured products

“in Europe, the creativity of the marketing brochures of these products is a key feature of the market”

“Financial institutions appear to rely frequently on analogies and powerful metaphors in the marketing material of retail structured products, to draw investor’s attention to the headline rate. (…) virtually all product names are related to one key metaphor stressed by Zaltman (1997): transformation, journey, balance, or resource.”

Measures

Headline rate: the annual return the investor gets in the best scenario. So: yearly return in best possible scenario. (Note: “no significant relationship between the headline rate and ex post performance, which suggests that the best scenario did not materialize frequently.”)

Three measures of complexity (note: “text descriptions not affected by changes in disclosure requirements, such as back testing and warnings”):

- Number of features: count the number of features in the final payoff formula of each product

- Length of the text description: count the number of characters

- Number of scenarios: count the number of “if” and “when” in the text description

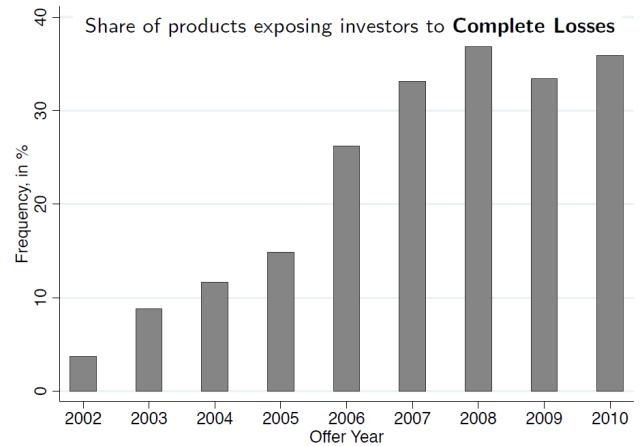

Risk: the structured product does (1) or does not (0) expose investors to complete loss of their investments.

Three Trends

[1] Headline rates depart from the level of interest rates when interest rates decrease. Relatively higher headline rates as interest rates decrease. The spread between product headline rates and interest rates increases when interest rates are low.

a decrease of 1% in the benchmark interest rate corresponds to a deviation of 0.64% of the headline rate from this interest rate. Banks offset two-thirds of the decrease in interest rates in the headline rates.

[2] Product complexity increases significantly, with no discernible drop during the global financial crisis.

[3] The fraction of products exposing investors to complete losses increases significantly. The share of risky products increases over our sample period.

Products offering high headline rates are both riskier & more complex

Markups & performance

“Both products offering high headline rate and more complex products yield higher markups to the banks that issue them. These ex ante higher markups translate into lower ex post performance for more complex products”

the average estimated yearly markup [based on N=141 Euro50 products] in our sample is 0.76%. Including disclosed entry and management fees: 1.4%.

Adding one additional feature in a payoff formula translates into an increase in the yearly markup of 0.34 percentage points

Adding one additional scenario increases yearly markup by 0.2 percentage points.

Adding 100 characters to the length of the description increases yearly markup by 0.13 percentage points.

In addition, products exposing investors to complete losses appear more profitable. Products that expose investors to complete losses offer a significantly larger markup: 0.78 percentage points per year.

negative correlation between product complexity and performance. Adding one payoff feature reduces the yearly return by 0.58 percentage points.

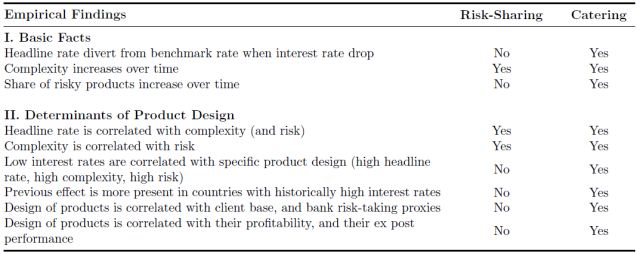

Risk-sharing or Catering?

Results consistent with banks catering to yield seeking investors through complexity (and shrouding):

Our results support the view that banks design complex products to cater for yield-seeking investors. Our findings raise questions about the adequate regulation of complex instruments and investor protection in retail finance.